Broadleaf Arrowhead A Wetland Edible

Introduction:

One of nature’s hidden treasures, the broadleaf arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia), is an interesting . This wetland plant not only captivates us with its distinctive appearance but also its edible tubers, seeds, and young shoots. Join me as we delve into the realm of this edible plant.

Common Names:

This versatile plant goes by several common names, each reflecting its various features and cultural significance. Among the most widely used names are “broadleaf arrowhead” and “duck-potato.” The term “arrowhead” is derived from the shape of its leaves, which resemble the tip of an arrowhead. Additionally, the name “duck-potato” is inspired by the fact that ducks and other waterfowl frequently feed on the plant’s tubers.

Description of the Plant:

The broadleaf arrowhead plant boasts a distinct appearance that makes it easy to identify and appreciate. Let’s dive into its key characteristics:

Foliage:

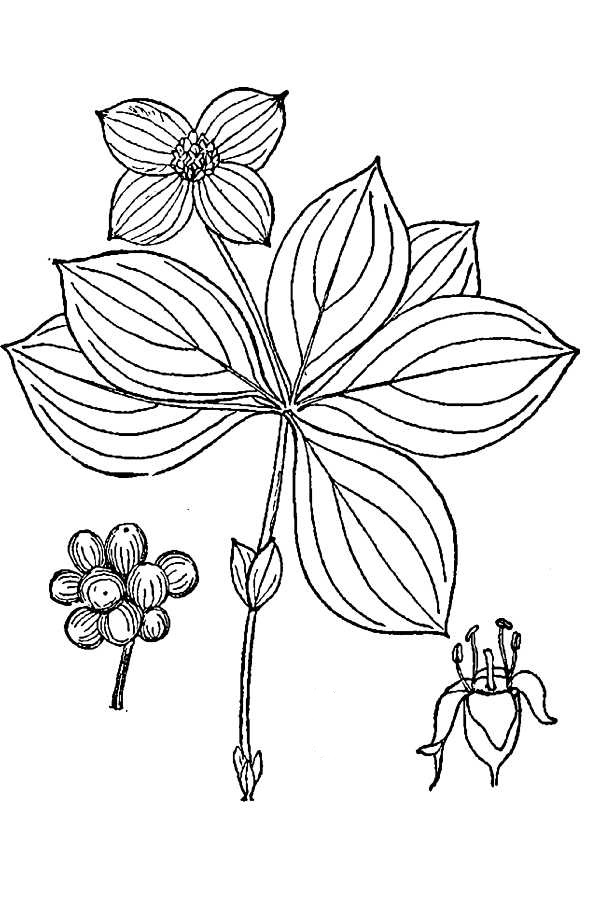

The arrowhead-shaped leaves, typically measuring 4” – 10” long, sprout on long stalks emerging from the water’s edge. The dark green leaves feature prominent veins and have a glossy texture. Their unique shape gives the plant its common name, “arrowhead.”

Flowers:

In the summer months, broadleaf arrowhead blooms with delicate white flowers that rise above the water’s surface on long, slender stems. These flowers exhibit three petals and a yellow center, adding a touch of elegance to the plant’s overall appearance. From August to October round clusters of seed casings develop.

Tubers:

Perhaps the most enticing feature of the broadleaf arrowhead lies beneath the water’s surface. The plant develops underground tubers, which are swollen, starchy structures that store nutrients and energy. These tubers can range in size from a few inches to over 5 inches in diameter. Their shape is elongated and somewhat reminiscent of a potato, hence the name “duck-potato.” These tubers serve as an excellent food source when foraging.

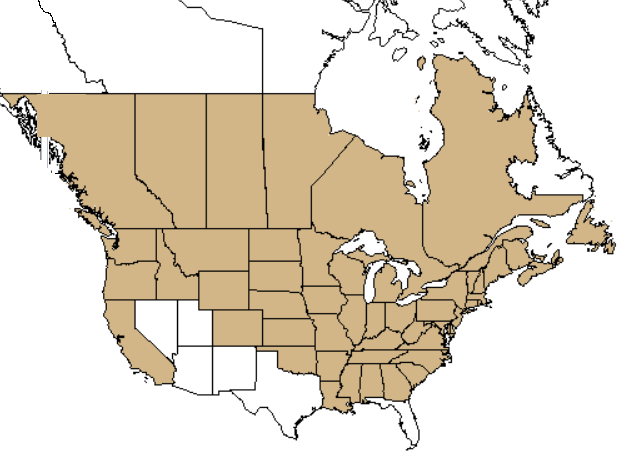

Territory:

The broadleaf arrowhead, like the cattail, is native to North America, where it can be found in a wide range of locations, including Canada, the United States, and Mexico. It thrives in both temperate and subtropical climates, allowing it to occupy a vast territory.

Habitat:

This versatile plant is predominantly found in wetlands, including marshes, ponds, lakes, and slow-moving streams where it can be found alongside pickerelweed. It demonstrates a remarkable adaptability to different water conditions, from shallow, still waters to those with a moderate current. The broadleaf arrowhead has even been known to establish itself in muddy or partially submerged areas, displaying its ability to colonize various habitats.

Edible Parts:

One of the most intriguing aspects of the broadleaf arrowhead is its edible nature. The plant offers several edible parts, including its tubers, young shoots, and seeds.

Tubers:

The tubers of the broadleaf arrowhead are the most harvested and consumed part. These underground, potato-like structures are rich in carbohydrates and offer a mild, nutty flavor. They can be harvested in late summer or early autumn when the plant’s energy is concentrated in the tubers.

Young Shoots:

The tender young shoots that emerge from the water are also edible. They can be harvested in spring and early summer and have a flavor like asparagus.

Seeds:

The seeds of the broadleaf arrowhead are small and can be ground into flour or used as a thickener in soups and stews. However, they are less commonly harvested compared to the tubers and shoots.

How to Harvest:

Harvesting broadleaf arrowhead requires some careful consideration to ensure sustainability and minimize ecological impact. Here are some guidelines to follow when harvesting:

Tubers:

To harvest tubers, gently loosen the soil around the base of the plant and carefully lift them from the mud. Select mature tubers, leave smaller ones for future plant growth and reproduction.

Young Shoots:

Harvest young shoots by cutting them close to the base of the plant. Choose shoots that are about 6 to 10 inches tall for optimal tenderness.

Seeds:

When collecting seeds, wait until the seed heads are mature and brown. Shake the seeds loose and separate them from the chaff by winnowing or using a sieve.

Cooking and Consumption:

Once harvested, the tubers can be cooked and enjoyed in various culinary applications. They can be boiled, roasted, mashed, or added to soups and stews, providing a nutritious and flavorful addition to your meals.

Young shoots can be eaten raw, added to salads, or steamed and boiled.

Seeds can be dried and ground into flour.

Conservation Status:

The conservation status of the broadleaf arrowhead is of concern in some regions due to habitat loss and degradation caused by human activities. Although it is not globally threatened, it is important to be mindful of the local regulations and guidelines regarding the harvesting of wild plants. It is advisable to obtain permission from landowners or consult with local conservation agencies before harvesting broadleaf arrowhead or any other wild edible plant.

Notes of Interest:

Indigenous peoples in North America historically relied on the broadleaf arrowhead as a food source and used it for medicinal purposes.

Some wildlife, such as waterfowl and beavers, also consume the broadleaf arrowhead, contributing to its ecological importance.

The Lewis and Clark expedition depended on the plant when they were in the Columbia River basin.

Know the Plant: Familiarize yourself with the characteristics of broadleaf arrowhead, paying special attention to its distinctive leaves and tubers, to ensure accurate identification.

The emergent foliage of this species provides cover for the same animals with the addition of fish and aquatic insects.

A single plant can annually yield up to 40 tubers.

Picture of plant: Robert H. Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. 1992. Western wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. West Region, Sacramento.