Ruby-Throated Hummingbird

General:

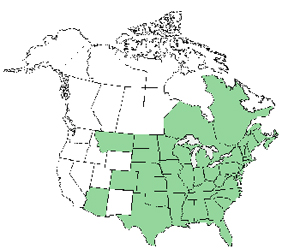

The Ruby-Throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris,) is one of my favorite backyard sightings, due to its brilliant plumage and spirited behavior. Before you can catch a glance, this acrobatic and energetic bird is usually on its way to the next blossom. This hummingbird has the greatest breeding range of all hummingbirds in North America and occupies much of the eastern United States and Canada during the spring and summer months. By providing the right vegetation and features in your backyard, you may be lucky enough to share your yard with this lovely species.

Description:

The Ruby-Throated Hummingbird is named for the metallic ruby-red throat patch found on the throat of the male hummin

gbirds. Both sexes have iridescent green plumage on their backs and heads and white undersides. This species of hummingbird has the lowest number of feathers ever found on any bird1. Females may be distinguished from males by their dull gray throats. The tails also differ between sexes, with forked tails

present on males and white-tipped square tails on females. Young Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are similar in appearance to adults, except for fewer red feathers on the throats of adolescent males.

Adult hummingbirds reach 3” to 4” in size, averaging 3.5 grams in weight2. Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds have long bills and tongues, used to drink nectar at an average of 13 licks a second. The tongues are grooved to aid in nectar collection and have fringed edges to help collect insects. This acrobatic flyer has short legs relative to their body length, making walking and hopping difficult and inefficient. Possibly the most unique physical attributes of the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird, besides for the red plumage on the males, are the wings. These tiny and delicate appendages are able to beat an average of 53 times per second, creating this bird’s distinctive “humming” noise. During flight the number of beats per second may be 78 times a

second and as high as 200 times a second during a dive (a display used in mating)3. Because of these extreme levels of activity and the tendency to ‘hover’ while eating, Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds have very high metabolic rates. The metabolic rate of these birds at rest is estimated to be 20.6 calories per gram per hour. In addition to their signature hovering, these petite birds are able to fly upside-down and backward.

On average, adult male hummingbirds live to 5 years of age and females live to 9 years in the wild. This species experiences a high mortality rate possibly because of the extreme energy demands of behaviors including breeding displays, migration, and defense of territory, leading to extensive weight loss4.

Ruby-Throated Hummingbird is a solitary species and typically only interact for breeding or territorial purposes. Male hummingbirds are territorial, using vocalizations to ward off intruders. If an intruder enters another male’s territory, the defend ing male will make a single note, repeating at higher and higher volumes until the intruder retreats. If the vocal warning is not successful, male hummingbirds are known to chase and physically attract other males (using their beaks and feet.)5 In addition to vocalizations, male and female Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds may communicate with and understand olfactory and visual cues. These birds can see the visible light spectrum as well as the blue-violet range. Developed vision along with their sense of smell helps these hummingbirds identify food sources.

ing male will make a single note, repeating at higher and higher volumes until the intruder retreats. If the vocal warning is not successful, male hummingbirds are known to chase and physically attract other males (using their beaks and feet.)5 In addition to vocalizations, male and female Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds may communicate with and understand olfactory and visual cues. These birds can see the visible light spectrum as well as the blue-violet range. Developed vision along with their sense of smell helps these hummingbirds identify food sources.

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are diurnal, most active during the day. When temperatures drop below optimal levels, hummingbirds enter hypothermic torpor in order to conserve energy. Hypothermic torpor is a state similar to hibernation, allowing a hummingbird to conserve energy through a lowered body temperature and slowed body functions6.

Populations of Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are wide spread and numerous, with an estimated 7.3 million birds worldwide. This species has never experienced any serious threats and is protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty between the U.S. and Canada. As with all hummingbird species, the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird is part of Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species7.

Habitat:

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds fulfill an important role in their habitats, pollinating flowers, shrubs and vines. This symbiotic relationship is so strong that some species of plants have adapted to cater specifically to these small birds. Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are migratory, inhabiting northern habitats during their summer breeding season and tropical habitats after migrating south for the winter. Preferred habitats include deciduous and pine forests, mixed woodlands, orchards, flowering gardens, parks, overgrown pastures, and citrus groves. The Ruby-Throated Hummingbird selects habitats that are close in proximity to water sources such as marshes or streams, to ensure abundant insect supplies8.

Males establish territories that offer food supplies, protection and mating opportunities. Some males have been known to establish a breeding territory distinct from their primary territory when food sources in the primary territory were not sufficient to support mating activities. These separate areas may be as far as two miles apart. Males are defensive of their territories and typically locate their territory at least 50’ away from a territory of another male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. Territories of Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds may overlap with those of other hummingbird species. In these instances, the male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird will become submissive9.

Within their habitats, Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are vulnerable to birds-of-prey (including blue jays which feed on nestlings) and, most often, house cats.

Location:

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are a migratory species. Between February and May these petite birds fly north to their breeding grounds located across the eastern United States and Canada, east of the 100th meridian. Between July and October Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds embark on a southern migration to their winter grounds that extend from southern Florida south to Panama and the West Indies. This species primarily winters in Central America. Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are capable of a nonstop, 500-mile flight across the Gulf of Mexico and may go so far as to double their body weight in preparation. The migration of this species coordinates with the blooming schedules of flowers.

Diet:

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds are omnivorous, feeding on flowers and nectar as well as insects. Adult hummingbirds require an immense amount of calories to support their behaviors and must consume approximately twice their body weight a day. They are most often spotted hovering over flowers as they lick the nectar, consuming approximately half their body weight in sugar a day, spread between five to eight feedings10. Preference has been shown for red flowers, but hummingbirds consume a variety of other flowers and nectar from wildflowers and flowers from shrubs and vines, as well as tree sap (collected from wells excavated by tree-boring bird species.) Insects are collected from sap wells and vegetation and include mosquitoes, small bees, gnats, small flies, aphids, spiders, caterpillars and insect eggs11.

If you are looking to attract hummingbirds to your garden, here is a variety of plantings you may consider:

Flowers:

Begonia, Century Plant, Butterfly Weed, Columbine, Delphinium, Fox Glove, Dahlia, Geranium, Impatients, Lilly, Petunia, Phlox, Snapdragons, Verbena, Sweet William

Vines, Trees, Shrubs:

Honeysuckle, Trumpet Vine, Morning Glory, Butterfly Bush, Rose of Sharon, rosemary, Tulip Poplar

Hanging a hummingbird feeder is also a great way to attract these beautiful birds. Fill your feeder with a concentrated sugar solution (roughly 4 parts sugar to 1 part water.) Boil the mixture until the sugar is fully dissolved. Remember to clean your feeder often, especially during extreme heat. The sugar solution should be changed every few days, especially during high temperatures because heat can cause this solution to spoil.

*Do not use artificial sweetener or honey in your feeder. Honey can ferment and cause hummingbirds to become sick and sweeteners contain no nutritional value13.

Reproduction:

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds breed while in their northern habitats between March and July, the height of breeding occurring in mid-May. This species inhabits a larger breeding range than all other hummingbird species in North America and is the only species of hummingbird that breeds east of the Mississippi14.

Both male and female Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds take several breeding partners during a given season, although no long-term breeding pairs are established. After copulation pairs separate and females assume all parental duties.

Male Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds return to breeding areas in the spring to establish their territories prior to females’ arrivals. Upon entering a male’s territory, a female will be courted with an acrobatic display: a showy display of red throat plumage and diving displays with males flying in loops above the females. If a female shows interest by perching, the male will proceed by flying in fast horizontal arcs just feet in front of the female. Females may give their final consent by emitting a “mew” and displaying a posture of cocked tail feathers and lowered wings15.

Females are solely responsible for selecting the site for and building a nest. Nests are typically attached to a down-sloping branch by pine resin, below a shelter of leaves, 5’ to 20’ off the ground or a stream. Common trees to find hummingbird nests in are oak, maple, poplar, birch, beech, spruce and pine. Nests are constructed of thistle, ferns, young leaves, moss, dandelion and milkweed down, spider and caterpillar webs, and bud scales and decorated on the exterior with lichen (possibly to provide camouflage.)

Females lay, on average, 1 to 3 small white eggs. After two weeks of incubation, the young birds are born and will be fed by their mothers in the nest for approximately 3 weeks. The chicks leave the nest about 20 days after hatching and reach sexual maturity at 1 year of age. In a single breeding season a female may have several broods.

Notes of Interest:

While hummingbirds don’t require a source of water for drinking, providing a water feature in your garden may help attract these beautiful birds. Including a fountain, pond, birdbath, waterfall or mister in your garden may increase insect populations and make your space more attractive.

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds were a prized specimen in the nineteenth century due to their beautiful plumage. Although these birds were commonly hunted and a coveted prize, this species never became threatened and numbers stayed strong and stable16.

Footnotes

1. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

2. http://plants.usda.gov/pollinators/Ruby-throated_hummingbird.pdf

3. http://www.wvu.edu/~agexten/wildlife/hummer.htm

4. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

5. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

6. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

7. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

8. http://plants.usda.gov/pollinators/Ruby-throated_hummingbird.pdf

9. http://plants.usda.gov/pollinators/Ruby-throated_hummingbird.pdf

10. http://www.wvu.edu/~agexten/wildlife/hummer.htm

11. http://plants.usda.gov/pollinators/Ruby-throated_hummingbird.pdf

12. http://www.wvu.edu/~agexten/wildlife/hummer.htm

13. http://www.wvu.edu/~agexten/wildlife/hummer.htm

14. http://plants.usda.gov/pollinators/Ruby-throated_hummingbird.pdf

15. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

16. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archilochus_colubris/

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birds/ruby-throat-hummingbird/

http://plants.usda.gov/pollinators/Ruby-throated_hummingbird.pdf

http://www.wvu.edu/~agexten/wildlife/hummer.htm

http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Archiloch

Back to Birds page

ing male will make a single note, repeating at higher and higher volumes until the intruder retreats. If the vocal warning is not successful, male hummingbirds are known to chase and physically attract other males (using their beaks and feet.)5 In addition to vocalizations, male and female Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds may communicate with and understand olfactory and visual cues. These birds can see the visible light spectrum as well as the blue-violet range. Developed vision along with their sense of smell helps these hummingbirds identify food sources.

ing male will make a single note, repeating at higher and higher volumes until the intruder retreats. If the vocal warning is not successful, male hummingbirds are known to chase and physically attract other males (using their beaks and feet.)5 In addition to vocalizations, male and female Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds may communicate with and understand olfactory and visual cues. These birds can see the visible light spectrum as well as the blue-violet range. Developed vision along with their sense of smell helps these hummingbirds identify food sources.